Warwick Bridge Mill is a community benefit society. The mill is water-powered and produces traditional stoneground flour. The society’s mission statement is “Grain to Loaf”. Having pretty well covered end-to-end bread production with their on-site bakery, the next item on their agenda is oats: rolled oats (like muesli) produced with oats straight from the farm.

Partnerships

It’s a tough world these days for small scale producers generally, and heritage producers in particular. Warwick Bridge Mill has been through the wringer recently, and has re-established itself owing to a large amount of good will from all sides, and a huge amount of enthusiasm and energy from their team.

Nobody can do everything by themselves, and trusted relationships are essential to make the mill a viable proposition. Even Lovingly Artisan in Kendal, who have taken the bold steps of milling their own grain to make their own bread flour, have partnered with trusted farmers to do the actual growing of the grain.

Milling

The same farmers who are working with Lovingly Artisan use Warwick Bridge Mill to grind their grain for one of their customers. This is how networks build and prosper in the heritage world. But Warwick Bridge’s main focus is on grinding for their own range of bread making flours for retail from the mill and for use in the on-site bakery.

Boulting

Unlike the Heron Corn Mill, where all the flour is sold as 100% wholemeal, made with the whole grain and no bran taken out, Warwick Bridge decided to follow the customers’ tastes and produce white flour. This means the bran has to be removed by sieving, or “boulting”. The Heron has a very old boulter on the ground floor, but it is well past its sell by date. Warwick Bridge have invested in a sparkling new machine to sieve their flour. It is made to a very traditional design with 3 interchangeable sieves of varying mesh sizes. As the sieve rotates, the meal moves along the cylinder and the different parts get separated out into the 3 hoppers below and finally on into 3 sacks - flour, middlings and bran.

This looks like the bran bin…

Under each bin there is a sack…

The numbers on these sieves indicate the degree of fineness of the mesh…

With so much white flour being produced, there is a large by-product: bran. I don’t know where they sell this, but it clearly won’t sell for anything like the price of flour. Typically, a roller milling operation takes 100kg of grain to produce 72kg of white flour, with 28% of bran and wheatgerm being removed in the milling process. Sieving should hopefully leave at least some of the wheatgerm behind, as well as some of the smallest bits of bran, but losing a quarter of the input must push up the cost of turning wholemeal flour into white flour. The customer is unlikely to want to pay for white flour as a premium product when compared to wholemeal flour.

Baking

Just as the Heron Corn Mill saw bread making in the shepherd’s hut as a vital part of the plan, Warwick Bridge’s vision, from the early days when the restoration work was being considered, included an on-site bakery. This has taken lots of cooperation from many sponsors and, I imagine, steely determination from the team. But they’ve managed it. They have a full-time baker and a hard core of baking volunteer-trainees.

The professional double deck oven was bought second hand and gives the baker a distinct advantage over the home baker by having a separate “bottom heat” control to help get a big oven leap…

There is a small mixer (known as “R2-D2”), a larger two-speed mixer and a bread slicing machine all of which were acquired through trade contacts.

This is R2-D2…

This is the slicing machine. I remember one of these in a high street bakery in Liverpool many years ago. When you pull the handle, 20 hacksaws descend onto the top of the loaf and slice it in one swift and noisy action…

The bakery has been nicely fitted out on a tight budget and a wide range of breads, cakes and biscuits rolls off the production line regularly. Some bread is sold in the bakery shop, and some on markets across quite a wide area. They have a delivery van for use on market days. There is a strong local following for the bread, largely sourdough, because the community understands that it truly is “their” bakery.

Rolling

Of course wheat, rye, spelt and barley weren’t the whole picture for corn mills in the old days. Like the Heron, Warwick Bridge has always handled oats as well. There is more to oats than meets the eye. As you have probably heard Iain say at the Heron Mill - “groats are oats without their coats”.

The pair of stones nearest the drying kiln at the Heron Mill are lightweight stones specifically for removing the husks, or “coats” from oats. They aren’t working now, but when they did they would be set to operate gently, with a fairly large gap between the top runner stone and the lower bed stone. With no great weight being applied, the oats didn’t actually get milled into oatmeal, just pressed enough to crack the shells. The next stage would be to pass everything through a winnower to blow the shells off, leaving the undamaged groats behind. These would then go into a heavier pair of stones to be ground into oatmeal.

Warwick Bridge are aiming at rolled oats rather than oatmeal and they have a modern rolling machine…

With no working oat-cracking stones, Warwick Bridge are currently buying in ready shelled groats to roll for muesli. But they are not happy with the flavour of these partially processed oats, and they want to buy whole oats and process them themselves. This is where the Near Far Heron project comes in.

Cracking

Stuart and Steve visited Warwick Bridge Mill in the middle of May to take a look at the old oat stones at Warwick Bridge Mill. Was there any chance of bringing them back into operation, to allow end to end oat handling on site? The first job was to discuss the scope and objectives of their visit.

These are the stones in question - floor mounted, with oats fed down from the floor above via a hopper and the stones driven from machinery on the floor below…

Stuart and Steve’s mission, should they choose to accept it, was to open the stones and inspect them. If all the parts were there and the surfaces of the stones were in good condition, then maybe it could all be made to work again. But just to expose the stones was a complicated job which took the pair of them till mid afternoon! Taking the hopper off exposed the horse (the wooden frame that supports the hopper) and the damsel (the metal piece on top of the drive shaft that taps the shoe and drops oats into the eye of the stone)…

Then off with the horse…

With the damsel out of the way they could finally get at the stones…

This is where the cracked oats are supposed to fall out of the side of the stones…

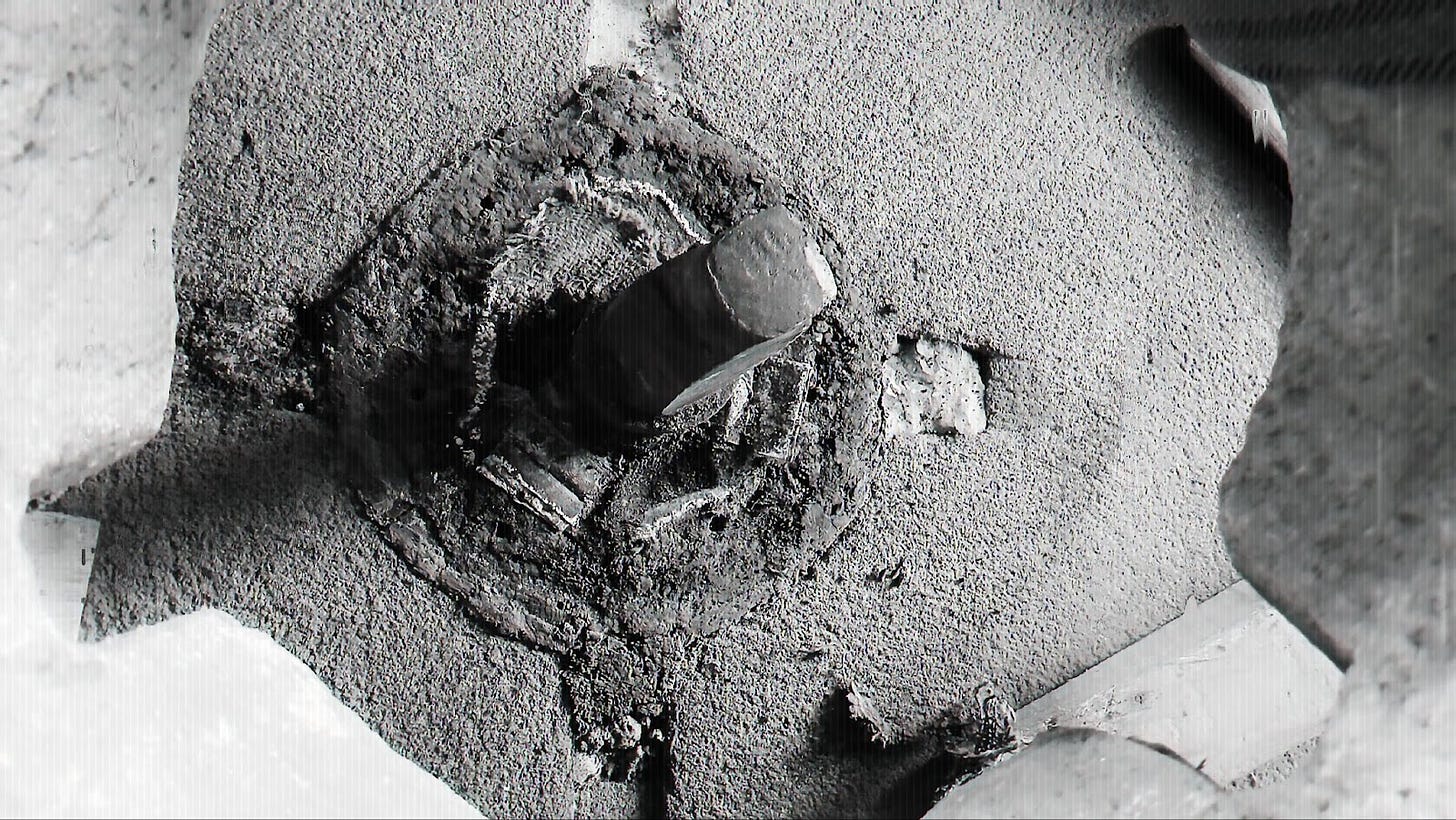

Some brute force was needed to make sure that the shaft could turn and that the rynd (the three-sided metal piece that supports the runner stone) was not stuck...

Get out the WD40!

Then the old opposing wedges technique again to open up a chink between the stones…

Next the lifting tackle had to be hung from a beam in the floor above. This involved a bit of creative carpentry, but eventually the runner stone could be lifted up. Keep your eye on the stone - it moves slowly…

That exposed the whole of the rynd and the shaft coming up through the bedstone…

Everything is in surprisingly good condition given the time it has been out of operation. Both stones have good smooth surfaces - no furrows on oat stones as they are not intended for milling.

The shaft may need its surrounding wood replacing but is otherwise sound…

The rynd and a metal mounting plate are OK…

So all in all, things look good for this project. Oats may well be cracked at Warwick Bridge Mill again!

Time to put everything back together again.

Building a mill is a bit like assembling flat-pack furniture: there’s always one bit that gets left out!

The future

Stuart and Steve will be reporting on their findings at Warwick Mill, and if they give it the thumbs up, a plan will probably be drawn up to allocate time to work on the stones. And then who knows? We may all end up eating 100% home-made Warwick Bridge Mill muesli for breakfast!

Curious objects corner

What do you think these strange hoops are?

They are magnets. The idea is that if there are any metal bits like old nails in the grain, the magnets will catch them as they fall down the shute and so stop them getting into the stones where they could cause some damage. Perish the thought that they might get into the flour!

You may have a similar magnetic device next to your boiler, to catch any rusty bits that have come off your radiators and stop them getting into the boiler.

Watching Stuart and Steve at work, is better than any television documentary. Restoration of ancient mills in modern time is truly educational.